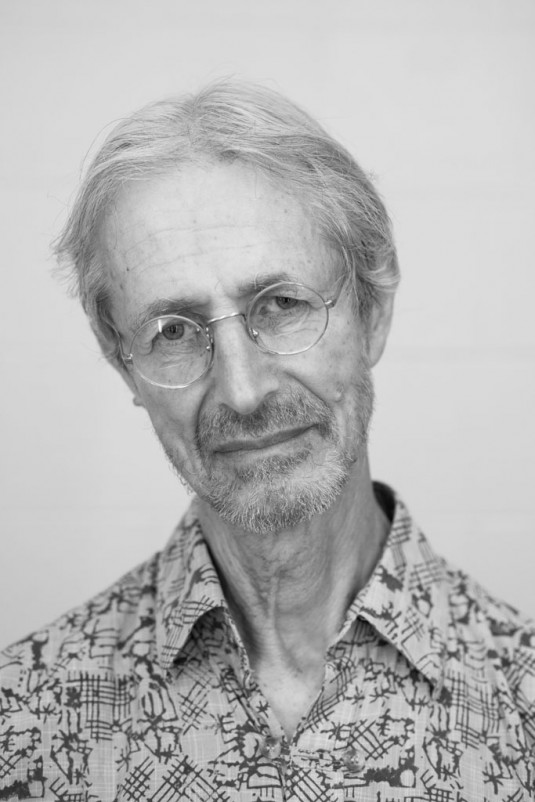

David Shapiro del Sole: Building empathy through stories

David Shapiro del Sole was born in New York and came of age during the Vietnam War. His story (so far) is a testament to finding your own way amid social and political tumult. David now lives in Bowral in New South Wales, Australia, where he has set up Highlands Counselling. It’s a place to go if you’re hoping to really be seen and heard. And most of us do yearn for this. David generously shared his story with me with honesty and humour. Here it is – enjoy!

Jess: Can you tell me a little bit about yourself? Where did you grow up, what was your childhood like and what led to the here and now?

David: I was born in the United States in New York in an area called Brooklyn. That’s where my father was born and grew up; my grandparents on both sides were Jewish. My paternal grandparents came from Russia and my maternal grandparents came from Hungary. I don’t remember my first years in New York. At about the age of two my parents moved because of my father’s work down south in the US. The reason why that was significant for my parents and for me was that Dad came of age during the Depression. He got involved in radical politics so he lost his job in New York because he got blackballed; it was one of the reasons why we shifted. So we went down to the deep south of the US to a small town with a population of 200 people. 190 of the 200 were black and the 10 who ran the town were white. We spent four years there. That was my learning of language so I can remember having a really strong southern accent.

And then we moved around a lot. We moved to the mid-west for a couple of years. That made a strong impression on me because my Dad had little businesses but my Mum – to make extra money – cooked dinner for the foreign students at the local university. On the one hand, because I was an only child, dinnertime was quite active and to me very exciting. There were students from France and South America and Israel and it introduced me to the larger world. We moved back to New York when I was about eight years old. For a number of years we lived with relatives because we didn’t have our own place.

Growing up in New York was a bit of an education in cultural diversity. That became a strong stream in my education and how I see life.

Jess: So what brought you back to New York?

David: My Dad was constantly trying to avoid 9-to-5 jobs and working for people, so he started a series of his own businesses, all of which lasted anywhere from six months to a couple of years and then went belly up. My Dad (this says something about me, too) was at the dreamer end of the spectrum rather than the practical end. So we lived with relatives in New York where my Dad again started another business. We lived behind a shop where my parents made some artistic things. It was an old Jewish neighbourhood and there was some sense that the greater part of the world is Jewish because that was my experience growing up. When I got older I realised the Jewish community was a minority rather than being the world’s population. Growing up in New York was a bit of an education in cultural diversity. That became a strong stream in my education and how I see life.

Then I did the usual kind of thing; I went to high school and university, which you were expected to do. The Vietnam War came along and I was of age. I had finished university and I was called up. I wasn’t quite sure what to do. In the end I left the country and became a draft dodger and went to Canada.

Jess: You mentioned that you went to university, what did you study?

David: I should say that I went to a few universities [laughs].

Jess: It took a while!

David: It took a while. Yes, it took twice as long as others. I started off as a science major. As you can probably tell in how I speak about my Dad, he was a strong influence in my early life. He had two sides: on the one side he was a very rational man, his conscious view of the world was, “If you think things through rationally you will arrive at the best answer”. Then, on the other side, which he didn’t particularly acknowledge but was by far the most important side of him for me as a kid: he was a very deeply feeling man, very kind, very gentle. As a teenager I picked up the rational scientific side and I had plans to go into biology. I spent about a year and a half thinking that, but I wasn’t connecting with it. Then I changed to history, and then I dropped out of school. I was close to my final year when I dropped out. That’s when I first got called up to go into the army. I don’t know if what was happening in Vietnam was quite a war yet, but it was really hotting up. And because there was the draft, ever since World War II, there was compulsory military service. When my turn came I quickly ran back to university and started doing literature.

I started to see myself as a potential writer and there was a school in New York called the New School for Social Research, which had some really cutting edge creative writing courses. So I went there for my final year and did some creative writing courses and got a degree in literature. When I finished I got called up again and it became a choice between the army and graduate school. I tried to avoid both and went up to Canada.

Jess: So what did you do when you were in Canada?

David: Before I answer that I should mention something that was significant. It was the mid-1960s at the time and I had a year abroad in Europe. I came back from Europe and everybody and their little brother was trying drugs of various sorts, me included, doing the usual dope smoking and Timothy Leary thing. I took some acid trips and had a couple of very, very traumatising experiences. At the same time I was being invited to join the US Army. All this stuff was happening at the social level in the country, it was real upheaval. Families were being broken up; there was conflict between one generation and the next. I was going through a personal crisis within myself, feeling completely lost. So when I went up to Canada I tried to get some legal advice about what my position would be there. No one really knew; the Canadian government was trying to sidestep the entire issue. At that time you could go to Canada without ID or a passport, so I just hopped on a bus and went over. I made some contact with some existing draft resister organisations in Canada and the US. They put me on to a place where I could get a job in Montréal. It was a local university library and the head librarian was sympathetic to draft resisters so I got a job working in the stacks. So that kept me alive.

It was the late 1960s and early 1970s. On top of everyone taking drugs, my friends were going off to India. They were studying Zen Buddhism, so I started getting interested…

At the time I was working under a false name because it wasn’t clear where the Canadian government was sitting. Technically they were saying they had no legal rights to send people back. It turned out later that they were in fact stopping people at the border and turning them back. So for about a year lived under a false name, but when the newspapers broke the story that the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) was doing stuff that wasn’t really legal it became safe and I became a Canadian citizen. At the time I was holding down two jobs; one at the library and the other door-to-door marketing, asking people what kind of beer they drank. I was still interested in writing so in my spare time I was trying to write.

It was the late 1960s and early 1970s. On top of everyone taking drugs, my friends were going off to India. They were studying Zen Buddhism, so I started getting interested in that kind of stuff. I went to yoga camps and attended Sufi meetings. Eventually I was trying a bit here and there of the various spiritual offerings. I went to a lecture on Steiner education and when I came away from the meeting I remarked that no one came up to me and said how glad they were to have me and would I be coming back. I felt no one made the effort to have me join up, which was such an enormous relief to me. And I thought, “Okay, I can come back”.

Jess: That’s a bit of an unexpected response, isn’t it?

David: Absolutely! Maybe it says something about the people from that particular movement. But to me that was a really important thing and, interestingly enough, Steiner started off as a philosopher of science. His basic foundation book is called Philosophy of Freedom. There is something going on there, I’m not quite sure what, but it spoke to me.

I spent another five or six years in Canada holding down odd jobs. I was also doing some writing. I tried to go back to university to do a Masters in Creative Writing at one of the universities on the West Coast. But I also found out there was this weird and wonderful course called Creative Speech, which came out of Steiner’s work. He had worked with his wife, an actress, and they created what they call Creative Speech together. There seemed to be an overlap between writing and putting that written mode into spoken form so, a year later, I was on a plane to Australia on a student visa to do this speech and drama course, which went for four years.

Jess: So where was that in Australia?

David: When I first arrived it was in a small studio in Cremorne [NSW] that had anywhere from 15 to 20 students in it. Then it moved over to Manly [NSW] and that’s where it was from the time that I was there. By the time I finished the course I met a woman who was one of my teachers. A few months after I finished the course we had a son so I applied for immigration because I only had a student visa and I wanted to stay. I needed to find a job. I got a very small educational grant from a high school in Mt Druitt. They wanted someone to come in and tell stories to their students once a week. And I thought, “Someone will actually pay me money to come and tell stories to kids?” So I started promoting myself and eventually got some community arts grants and spent the next seven years telling stories around Australia.

Jess: And now you earn your crust by listening to other people’s stories!

David: Yes, now I listen to stories. When I meet up with people I knew 25 years ago and they ask if I tell stories anymore, I say, “No, but I listen to stories now”. It’s the same activity, sitting on the other side of the room.

Jess: In being able to tell so many stories in the first place you would have been listening, they need to have come from somewhere.

David: Absolutely. Since I’ve become involved in doing therapeutic work it’s become much clearer to me that listening is equally active as the actual telling. What is happening for the teller is equally dependent on the listener and vice versa. It’s a totally collaborative activity.

Jess: So how is it that you shifted from being the teller to the listener?

David: There is a gap in between. Eventually after about seven years the grants and the work dried up for me. It was the Howard era and most grants were disappearing. I was competing against the Bell Shakespeare Company to get bookings in schools. During this time I became a single parent. Because the work started to dry up I just thought, “Stuff it for now,” and I stayed home for about eight years being a parent. When my son moved on I went back to school again and got a degree in teaching English as a second language. I did that for about 10 years, and by this time I was ageing. I was always ageing but I was getting close to retirement age. I had friends who were working in the mental health field and a close friend of mine had just come back from Europe where she had studied with someone who began their own therapeutic model, strongly influenced by Jung’s work, and called Process Orientated Psychology. Some years later, I thought, “I’m going to try something different,” so I went and did a counselling course in Sydney and then when I finished I hung up my shingle. For the first two or three years I had one utterly devoted client. If it weren’t for her I would have given up long ago! I am eternally grateful to her for keeping the flame going.

Jess: So how long has Highlands Counselling been in existence?

David: Since I finished my course, so that’s five years now.

Jess: There seem to be some key philosophies that really inspired you, mainly Steiner philosophies and the Jungian approaches to psychology.

David: My first introduction to psychology was Process Orientated Psychology. Its founder, Arnold Mindell, had originally been a Jungian therapist and he took it to what he described as the next step of the Jungian approach. He did a lot of bodywork and what he discovered in observing our physical body was that you could read the physical body in the same way you could read dreams. He would sit there and watch you. He would look at how your hand is holding a glass and start having a conversation about that physical gesture. And because of my background in Steiner I was certainly open to the whole Jungian approach and to process work.

When I started doing the course somebody came in and gave a lecture on Carl Rogers. They showed us a video of Rogers and Fritz Perls, the founder of gestalt, and another fellow whose name I can’t remember. Carl Rogers sat there and there was something about him that was so intent in his listening. It was like he was listening to this person’s presence. I didn’t know what it was but I kept watching the video again and again.

Then I was married a second time and my second wife had died and I discovered some books she had. She had at least one of Rogers’ main books and I started reading it. He wrote as you would expect someone to speak – in such simple, conversational language. In all of my studies I hadn’t come across that at all. This guy was speaking to world conferences in language an eight-year-old could understand. I didn’t know if it was good or bad, but it really grabbed something in me. It was something that I trusted. So over the last five years he and those who have been his disciples and came out of his work have been inspiring me.

Jess: So would you describe yourself as a Carl Rogers disciple?

David: I’m too scattered to be anyone’s disciple. It’s like that experience of going onto the internet and being led from one place to the other. I tend to go back to that very basic experience of just listening to what the other person is saying, forget everything else, just being present to what they’re saying. I do come back to that, always.

Jess: I know you’ll have confidentially issues to think about, but in a broad sense what happens in your counselling sessions?

David: Even if I didn’t have confidentiality issues I would have difficulty in describing it! I at least try. I often come away feeling I haven’t done so well in just listening rather than bringing in my own history, my own story. While I know that it’s inevitable that I bring me to the meeting, I want to be as conscious as possible that my story doesn’t interfere with the story that you’re struggling to tell. So what do I do? I say, “Hi”.

I take it as my task to know who this person is because I think that is the foundation of what we call therapy or healing, this thing about knowing who I am, and knowing who you are.

Jess: That’s a good start! [Laughs.]

David: [Laughs.] If I get past that, I’m relieved. Will they respond? And as soon as that starts a huge part of it is unknown to me. I take it as my task to know who this person is because I think that is the foundation of what we call therapy or healing, this thing about knowing who I am, and knowing who you are. So if the other person can at least feel that my commitment is to get to know them, then the relationship starts to become something that is prized, is valued. It’s about seeing yourself and your environment as being of enormous value, which can be totally different to the message given to you by your family or community. If I can help with that, then I have a sense I’ve done okay.

Jess: In a roundabout kind of way what you’re saying is that what you bring to counselling sessions is that deep sense of empathy of looking deep, feeling deep, so that the person feels that they’re being seen and can recognise that they matter. How do you facilitate that process? Isn’t that a bit taxing on you?

David: I’ll go back to Rogers. He said, for him, there were three conditions for healing to happen. One was empathy, stepping into another person’s position, another one was what he called congruence and that is, in a more everyday way, called being upfront, being honest, this is who I am. I don’t sit in the therapist’s chair trying to give you an impression that is not me. So I have to be as free as possible of trying to be someone I am not. To the extent that I can do that, I can be present for the other and I can also step into what they’re telling me, I don’t have agendas. I think that carrying the least amount of my own personal baggage allows me to be empathic.

Jess: That’s interesting. “Baggage” can be a loaded term. But you grew up among all kinds of cultures and it sounds like you were exposed to diversity. You are also young in the 60s and you were aware of what was going on in politics and the Vietnam War. You mentioned that you lost your second wife, which must have been a traumatic grief. So you’ve got this breadth of experience that must be brought to the process. It’ll give you the empathy and a capacity to connect. All of that is going to come with you. Your experience would make you feel more ‘real’, more ‘human’, to your clients.

David: If I understand what you’re saying, it’s that baggage can also be a positive. Yeah, there’s baggage and there’s baggage.

[Laughter.]

Jess: Well, there’s baggage that hasn’t worked, and then there’s baggage that helps you.

David: That’s a really good point. Baggage has always had a negative connotation for me, and you’ve completely turned that around, so from now on I’m going to come into the room with heaps of baggage [Laughs.] I think you’ve helped me. How much do I owe you?

Jess: [Laughs.] Now, I wanted to ask about your Empathy Circle in particular. I’m curious to know what happens during an Empathy Circle session?

David: The Empathy Circle started about a year and a half ago; it came out of a program I was running for depression. And when it came to an end I asked if anyone wanted to continue not as a program but just as a group that meets every once in a while. About half a dozen people were interested in doing that. There was something about having the capacity to listen that seemed more and more important to me, which is why I called it the Empathy Circle. And what do we do? It really is very open. I play the role of facilitator but what’s talked about is up to the people who come. We go for a couple of hours and it just rolls along. I do other groups as well, but I’ve never come away from an Empathy Circle feeling that nothing has happened. I have had that in other groups but not in the Empathy Circle.

Jess: Is it mostly the same people on a weekly basis?

David: There is now a core group of about five or six and they connect outside of the group, as well now. They’ve gotten to know each other and have formed bonds. Something came up recently in the group; it was quite unexpected, in which someone was very distressed. At that moment, it could be said that I was not quick enough to act, not present enough, and so created something of an empty space. A number of the participants immediately jumped in to fill that space and took care of it. I certainly didn’t do that intentionally, one could say I stuffed up there, but looking down from above and seeing a larger picture, I could say, “David, you were fantastic!” [Laughs.] Quite unconsciously and unintentionally, of course. Some of those participants now have the experience of: “I come here as a person not just with difficulties, but I also have the capacity to help other people.” In terms of a therapeutic effect, that is crucial. Groups can offer that.

Jess: Each group has their own dynamics. One-on-one counselling can still be an atomised experience; you can still feel quite isolated with whatever issues you’re dealing with. In a group setting you have the opportunity to share your stories and be in the trenches together. Can you tell me a little bit more about the two men’s groups that you run?

David: They’re quite different. One’s been going for five years and that’s held at under the auspices of Wingecarribee Family Support. So I co-facilitated an eight-week program for grief but it was for men only. Some of the participants really started to bond with each other. They had never been to any kind of men’s group before and they asked if they could have an ongoing thing, so we started to have weekly meetings. Five years later it’s still going.

The other men’s group meets once a fortnight. The fellow who started the Harmony Centre in Mittagong started that. He had an interest in getting a men’s group and asked me whether I would be interested in facilitating and I said, “Sure”. It’s a somewhat different demographic. The men who come to that group don’t come because they have had mental health issues; they’ve come because their partner tells them they don’t know how to talk about their feelings. It’s somewhat different and so the conversation has a different flavour. I haven’t thought about this before, but is there a common theme between the two groups? I suppose the common theme is that – in this very fluid world where gender roles have been turned upside down in such a relatively brief space of time – where am I and what am I supposed to be doing?

Jess: It’s interesting because among women there is a tradition of swapping stories about pesky parenting issues. Men don’t usually have that kind of space marked out for them at that everyday level. They do when it comes to writing books, men are the public storytellers in patriarchal cultures. So we listen to men’s stories more often at that meta-level, but not at that everyday level. Do the men in your groups find it cathartic? Do those who keep coming back find it refreshing and relieving?

David: I think telling your story, whatever the gender of the person telling it, is therapeutic for the person telling it. When the Empathy Circle started it was a mixed group for the first six months, at the moment it’s all women. I think it’s fair to say – I might get some difficult feedback from the men who were in the group – that the men really had difficulty in keeping up with this facility that some of the women had to not only speak about their emotional life, but to have awareness of their emotions. On a certain level some of them really appreciated and respected it, but if they were thinking competitively, “Am I up to scratch?” then it is was going to be a very humbling experience for them. That was my take on why some of the men dropped away. I find as a facilitator in a men’s group, I often try to bring the conversation around to a more intimate, personal tone, whereas with women, I have to do that much less.

Jess: I often feel that men are trapped in a way, socially. It happens on both sides, there is an entrapment of some sort on both sides. For most men it’s emotions, and for most women it’s about feeling empowered in the public sphere.

So The Soul Spectrum looks at spirituality and soulfulness in it very broad terms. There is a strong undercurrent of spirit and soul going on in your life, but do you have spiritual practice?

David: Well, I run it by you and you can tell me if it ticks the boxes! [Laughs.] For years I would make attempts at meditation, it was one of those things. It wasn’t a requirement but it was certainly on offer in the Steiner circles. I would do it for a few weeks and think, “I’m not getting anywhere,” and give up. Then when I met my second wife she was very deeply involved in Vipassana and she was constantly going off to retreats. She was inviting me and sometimes it was even stronger than an invitation to do some meditation. I suppose it just gets back to this thing of feeling so comfortable in the group that made no effort to invite me to join. There’s something about groups that I find I’m very cautious around. So I didn’t begin to meditate in any regular sort of way until my wife died. It was a way to get in touch with something in myself but it was also about staying connected to her. I needed to because she died suddenly in the car next to me. As painful as the experience was, I knew that it touched on something that I didn’t want to lose; it had awakened something in me. I think you used the word depth or deep and it was that, it was the depth of experience. I thought, “This is bloody painful but I feel so alive”. So each morning, before I had breakfast, I would get up and do some Tai Chi, then I would sit and it was my 20 to 30 minutes, it was my time, and I’ve been doing that for years.

I read a book by a man who is a physicist who also wrote a book on the Dalai Lama. It was about contemplation and it had parallels with other things I was coming across in psychology around phenomenology that relates to listening and taking in as purely as possible the actual phenomenon. What’s going on there? Letting it speak to you.

Jess: It all sounds suspiciously like mindfulness to me!

As I grew up superficiality was worse than first-degree murder and depth is what makes life worthwhile.

David: When I think about soul my mind goes to soul music. I grew up in the US and it was the 1960s. I was never a big rock ‘n’ roll fan but I really liked soul music and I still listen to it. I was thinking what is it that grabs me and it has something to do with that term “depth”. I conveniently forgot to tell you I had mother issues. If you asked me what would truly drive me nuts and why I found it so difficult to be empathetic towards my mother, I would say it was her superficiality, in my eyes. As I grew up superficiality was worse than first-degree murder and depth is what makes life worthwhile.

So soul. Soulfulness to me is depth. There’s a Spanish poet, who won the Noble Prize in the 1950s: Juan Ramon Jimenez. I came across some of his poetry and I was blown away. I went to Spain and visited the place where he was born, a pilgrimage of sorts that I was drawn to do. I later came across a collection of his poems that I didn’t know called Animal of Depth. In one of his poems there is a line, “I am an animal of depth of air”. It struck me that putting side by side a word like depth that describes vertical measurement in space and air that is immeasurable and intangible.They seemed contradictory terms. For me it is the kind of depth we experience when we choose or are forced to deeply enter, to go down into our own experience – our own immeasurable, intangible being – that’s what I think of when I say the word soul.

Jess: Wonderful, thanks David!

* For more information about David Shapiro del Sole, please visit highlandscounselling.com.au

* For more information about Hamish Ta-mé, please visit www.shotbyhamish.com

‘herz’ by Jim Pettigrew

‘herz’ by Jim Pettigrew